HUMS 358, Modernist Paris and Moscow

Course Description

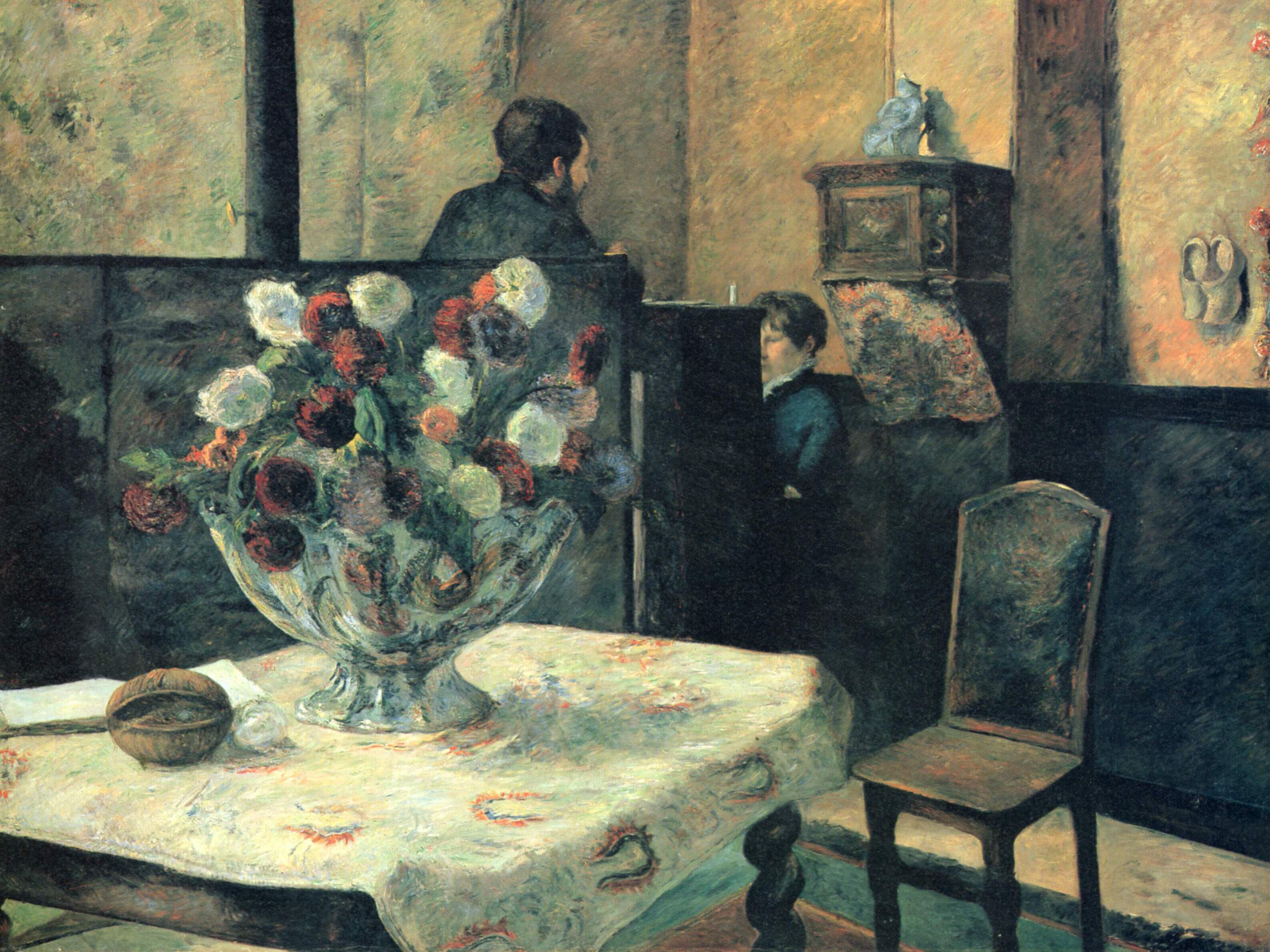

This interdisciplinary, comparative course unsettles the notion of Moscow’s marginality and Paris’s centrality from the viewpoint of early 20th century literature, visual art, film, performance, and architecture. The course demonstrates the ways in which Modernist movements in Moscow and Paris were intimately connected and mutually influenced through decades of artistic exchange and competition. Paradigm-shifting artists, writers, and cultural figures like Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Paul Robeson, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Le Corbusier, Langston Hughes, Marina Tsvetaeva, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Walter Benjamin are only a few points of contact between these two epicenters of European modernism. Both Moscow and Paris, sometimes at odds and at other times in collaboration, confronted political and aesthetic questions related to imperial conquest and exoticism, revolution and abstraction in art and language, liberations from race and gender, the march of war and technology, new conceptions of the body, urban imaginaries, and life lived as art. In this course, we explore these very topics in modernism through close reading and visual analysis of works by and/or related to Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Charles Baudelaire, Symbolists, Walter Benjamin, Futurists, Kazimir Malevich, Meyerhold, the Ballets Russes, Josephine Baker, Jane and Paulette Nardal, Constructivists, Alexander Rodchenko, Surrealists, Aimé Césaire, Négritude, Alexandra Kollontai, Sonia Delaunay, and Varvara Stepanova, among others.

No knowledge of Russian is required.

Led by

|

Professor Katerina ClarkKaterina Clark, a native of Australia, has taught at SUNY Buffalo, Wesleyan University, the University of Texas at Austin, Indiana University and Berkeley. Her present book project, tentatively titled Eurasia without Borders?: Leftist Internationalists and Their Cultural Interactions, 1917–1943, looks at attempts in those decades to found a “socialist global ecumene,” which was to be closely allied with the anticolonial cause. Ecumene here is taken in the modern sense to mean a far-flung or world-wide community of people committed to a single cause and engaged in discussions, lobbying and writing or filmmaking aimed at working towards a commons, at generating a common discourse, in this instance largely a Marxist-based one. The book looks at the interactions during the inter-war years of European culture producers with counterparts in Asia, principally in Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, Northern India, China, Japan and Mongolia. It analyses works generated in the name of this common cause as it follows the evolution of the putative ecumene over two decades. |